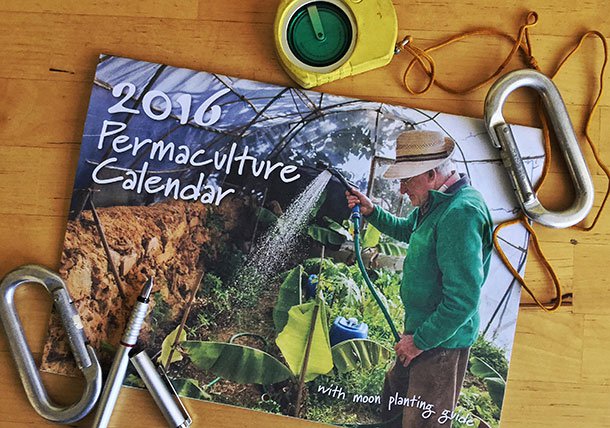

Long time permaculture practitioner and photojournalist Russ Grayson reflects on the tangible in a world of digital, sharing his experience of receiving a 2016 Permaculture Calendar in the mail

Long time permaculture practitioner and photojournalist Russ Grayson reflects on the tangible in a world of digital, sharing his experience of receiving a 2016 Permaculture Calendar in the mail

IT WAS a plain envelope. White. The type you post A4-size papers in. The address was handwritten. There was red a DO NOT BEND stamp on the front. Whatever was inside was flexible. I knew that because the post office has bent the envelope to get it into the mail box. On the back was a return address with a logo that looked like a stylised flower, and a handwritten greeting.

In these digital days I don’t get much mail like this now — they call it snail mail though that’s a term you don’t hear all that much anymore. So it was something of an arcane pleasure to rip open the paper envelope to retrieve whatever had been put inside by someone in some other place, some other town and carried across the country to me.

I gently tore the envelope open and out tumbled 2016 Permaculture Calendar. “That time of year again”, I thought.

The persistence of paper

How long has the Calendar been published now? I can’t pull the number out of my head and I’m not going to bother published, Richard Telford, to ask him such trivia. But let’s say it’s been awhile and in saying that let’s consider how printed calendars can do things their digital kin cannot, like hang from a nail in the wall. When it comes to calendars, paper persists.

The calendar used to be accompanied by a diary full of photographs that was something of a permaculture picture book, but that is no more. I note that in bookshops and stationers the shelf space taken by diaries, which was once considerable, is these days diminished. Diaries were devices to which you outsourced that part of your memory devoted to dates, times and schedules, but that’s what people now use those pocketable, multipurpose digital devices still anachronistically called ‘mobile phones’ for. I doubt the paper diary species will go extinct but the population is certainly less numerous and less diverse now.

The Permaculture Calendar’s month-to-a-page-view provides a comprehensive graphical overview of the weeks ahead, data entry into the little windows accompanying each date is made with a pen (does anyone write with pencils anymore?). But scribbling in the dates you need reminding of, like your partner’s birthday you are in a bad habit of forgetting, is only half the story. The other half is visual.

Photography the hook

I think it is the photographs that are the hook that catches people’s imagination and leads them to acquire a Permaculture Calendar. They reflect our permaculture back to us so we can see what people elsewhere are doing, and in doing this the photographs remind us that wherever we are we are all part of a scattered permaculture network of practitioners.

When I say that the Permaculture Calendar is a picture calendar there’s the risk that the photography-savvy will start thinking in terms of exposure, composition, tonal values, colour rendition, depth of field and angle of view. They will be wrong in looking for these things in the images, as the calendar is not about fine art photography. It is more photojournalistic in image style because the photographs capture and report the things people do. Although the images are well reproduced, it is not the quality of light or the quality of reproduction that matters most, it is the content (I note a little photojournalistic bias in saying this).

What you will also not find in the Calendar are photographs reproduced on the coated, glossy paper that characterise many other calendars. There’s two angles you can take on this. One is that the matt, non-glossy images do not display the photographs with the vivid colours of glossy papers and this you might find disappointing though not a reason not to buy the calendar. The other is that the matt paper is recycled stock and the coloured inks are vegetable-based. It comes down to photographic perfectionism versus environmental values, and here the Calendar reflects its own preference.

After the calendar spilled from its envelope I picked it up and flicked through, but I got only as far as January for there was something familiar… something familiar but not recent in that photograph… something about that red house at the end of that track. It was almost as I had been to that place. Then I realised I had, for it was the community building at Dharmananda in northern NSW, not all that far from Nimbin. Dharmananda is one of our early intentional communities — the precursors of what we now call ecovillages. That photo, for permaculture folk, comes from our dawn-time.

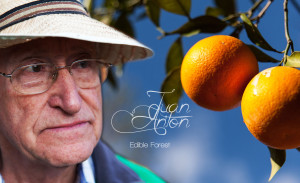

The photographs in the 2016 Permaculture Calendar are international, the image of Juan Anton’s edible forest garden igloo on the cover comes from Spain. Three of the images are those made by designer and publisher, Richard Telford.

The suggestions of images

Academics might analyse and argue about messages and implied meanings in photographs but photographers already know that and, like those who contributed to the 2016 Permaculture Calendar, they just get on with the job.

Permaculture is commonly associated with the growing of food in home and community gardens, however the April image is about something other than food production or, as David Holmgren calls it, garden agriculture. It depicts the enjoyment of nature, and the caption accompanying is is about the acceptance of calculated risk as a necessity for personal development.

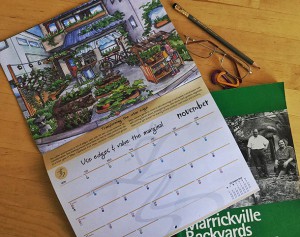

November’s image of a small home garden in Tokyo I like because it disrupts the format. It is an illustration, not a photograph. It also breaks the preponderance of rural imagery we find in the Calendar — Tokyo being one of the most densely-populated cities on our planet.

July, with the image of a woman making some kind of utilitarian object from natural fibre, reminds us of technology’s long tail. Long tail refers to the continued use of a technology or technique long after it has faded from everyday use through replacement by newer, probably improved technology.

Having set out on its long tail, the technology or technique is practiced by comparatively few people, perhaps as a hobby or craft because they have an interest in technological evolution or, manual work or, sometimes, out of deliberate preference for the technology as an everyday tool. Think blacksmithing, the use of animal traction on farms such as horse-drawn implements, using scythes to harvest grain and cut grass, buying music recorded as vinyl records rather than downloading digital files, using MS DOS (yes, improbable, I know).

Old tech, the month’s image reminds us in referring to the Festival of Forgotten Skills, is not necessarily inefficient tech and its use can be an educational, skillful and aesthetic practice. In this case it is being practiced, I assume, as craft, the fate of many skills that were once utilitarian.

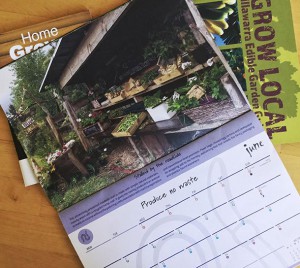

And now, here comes my bias. It’s June’s photograph of a roadside stall in Tasmania, down in the Channel country not all that far south of Hobart. I can’t put my finger on it but there’s something quintessentially Tasmanian about this image. Is it the quality of light? The produce on sale? The ambience suggested by the photograph? Or is it the continuation in Tasmania of what has been largely lost on the mainland (that’s Australia for non-Tasmanians). Or is it simply because I once used lived there and have seen such sights?

A reminder

Each month’s photograph in the 2016 Permaculture Calendar, like its earlier kin, is themed according to the 12 design principles developed by permaculture co-inventor, David Holmgren. The Calendar also caters for those into planting by moon phase. On the inside back cover there’s a clear, multicolour year’s calendar ready for you to block in clusters of times for those multi-day, multi-week activities as well as those important single days.

Sure, the 2016 Permaculture Calendar it is good for planning your year, but that’s not all. Hang it from a nail in the wall and it becomes something else that has nothing to do with making best use of our time. It becomes a reminder, not of dates, but of what matters most to us as permaculture practitioners… that’s the values the design system brings us… the networks we participate in… the permaculture ethics we try to live by… and how it is that we seek a better way to live through the principles of the permaculture design system.

2016 Permaculture Calendar

2016 Permaculture Calendar

- Produced in Australia on 100% recycled paper using vegetable based inks.

- Size: A4 (210mm x 297mm) opening to A3.

- Implementing permaculture’s third ethic— by redistributing 10 percent of net return to Permafund, Permaculture Australia’s public fund that makes grants available for activities that demonstrate the ethics and application of the principles of permaculture.