Russ Grayson’s review of the 2017 Permaculture Calendar

Russ Grayson’s review of the 2017 Permaculture Calendar

Originally published on the PacificEdge blog.

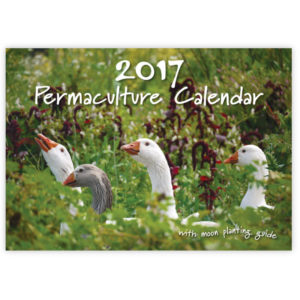

WITHOUT DIRECTION we drift like a ship with a broken engine. With a sense of direction we move forward. But to have direction we have to know where we have come from. We have to know where we are going. The Permaculture Calendar has become a means of knowing that. It represents the temporal framework within which we plan our permaculture journey. The Calendar is the engine of our permaculture ship and it is not broken.

Thanks to the work of Richard Telford, each year the Permaculture Calendar appears to document the work of some of the practitioners of this distributed network we call permaculture. In this review of next year’s calendar I want to look at two things:

- one is the role of photography, publishing and media in general in propagating permaculture and how that relates to the Permaculture Calendar

- the other is a philosophical question about the type of lifeways the images suggest as constituting permaculture.

On photography

Having just written that subhead I realise I have accidentally borrowed it from the writer, Susan Sontag, who wrote a book with that title. But… onto the value of photography.

The calendar demonstrates the value of photography in documenting this social movement of ours. It is no secret that the worldwide web has increased the importance of visual communications such as photography, however the use of calendars as visual media predates the web. Thus, the Calendar acknowledges the primacy of visual communication through photography and continues the tradition of the calendar as a medium for it.

It discloses in colour the creativity in permaculture. Through the photography appearing in the Permaculture Calendar over the years of its existence we view a history, a visual story of this design system of ours. The Calendars become a visual story of our collective accomplishments, the works of individual permaculture practitioners and also that of the organisations they set up. We can look back and see what we have done and in doing that we start to get a sense of the continuity, the ongoing history of our design system. If we keep the permaculture calendars over the years we can flick through them and in doing so see our story, or part of it, in full colour.

Permaculture Calendar 2017: the images

There are five photographs showing some aspect of gardening in the 2017 calendar, one about a technology made by hand, another on the craft production of a utilitarian kitchen tool, one about food, one about building and one about recovery after natural disaster.

Composting in February

February’s compost system that moves composting wastes downslope as they go through the composting process I know works because I have seen a similar system in use in a community garden.

The material degrades as it is moved downslope but because it is not exposed to the heat that a compost heap produces it does not affect the propagation potential of seeds that might happen to be in it, nor does it complete the composting process. The experience of the community garden I mention was that the partially-degraded material needs to be accumulated into a compost bin or system after being moved downslope. Here, it is exposed to the heat build-up that completes the process and allows the material to cure.

April’s homesteading

April’s image of food storage at a homestead, that avoids the use of electricity, shows the value of producing and storing surplus, though such a low-energy lifeway is available only to the few. There is nothing wrong with homesteading, of course, but modern lifeways militate against it.

Despite this, in the best tradition of permaculture people manoeuvre around the problem to adopt some of the elements of the homesteading lifestyle. My partner, for example, preserves fruit and other foods using Fowlers Vacola tech even though we live in a small apartment. Likewise, busy urban working people with no time to make bread the traditional way find a solution in technology with their own electronic breadbot, a bread making machine. Although this domestic automation of the breadmaking process might not appeal to traditionalist home bakers who roll, pummel and knead their bread dough, the breadbot offers home bakers a high degree of control over what goes into their food.

Food production in the home garden, where that is available, is another possibility although there is much to be said (and Bill Mollison said it) for buying your food from someone who has produced it responsibly through a food co-op, CSA (community supported agriculture) or the hybrid-CSAs/food hubs we have in the big cities. In so doing we contribute more to building the regional food economy than home growing does.

“We can also begin to take some part in food production. This doesn’t mean that we all need to grow our own potatoes, but it may mean that we will buy them directly from a person who is already growing potatoes responsibly. In fact, one would probably do better to organize a farmer-purchasing group in the neighborhood than to grow potatoes.”

…Bill Mollison.

October’s wheel

October’s wheel of ecological culture I find a somewhat contradictory concept. At one point on the wheel it states ‘technology backgrounded’. Yet, a little further on it states ‘energy powerdown — renewables’.

Why the contradiction? Because renewable energy systems are hi-tech, they use new types of materials and computerised, automatic control and distribution systems. If we want a society powered by renewables if follows that we want hi-tech.

For the most part the wheel is fine as a conceptual map of what its producers see as valuable in an emergent, resilient culture.

March’s farm

March’s image appeals to me most of all, perhaps. Not because it is astounding in any photographic sense but because of what it shows — a scaling-up of permaculture ideas in the city to produce food in bulk.

We realise this is already happening when we think of Hobart City Farm, Wagtail Urban Farm in Adelaide and the new Pocket City Farm in inner urban Sydney. These are small urban market gardens producing fresh food on a commercial scale. They are important not only because they enact Bill Mollison’s dictum of returning food production to the city, but because they create livelihoods in the new economy.

We know that the new economy emerges from the old, it uses the materials, the fuels, the knowledge of the old to create and build the production capacity, the tools, the technologies, the organisational forms of what will replace it. Small scale, intensively managed farmlets in the city like that in March’s photograph are one of those new systems visible in the old and they scale-up backyard and community garden food production and make it available to more people.

A brief philosophical question

Images in the 2017 calendar raise a philosophical question about permaculture. Looking through next year’s calendar I find the 12 photographs a celebration of gardens, food and the handicraft approach to life.

All of this is good and all of those skills valuable, however it comes across as being about past values from, as some might see it, the Nineteenth Century being transposed into the Twenty First. Someone, and I don’t recall who, once said that there is a lot of nostalgia in permaculture. They meant nostalgia for those past times, for the era of manual labour, for the handicraft approach to the provision of our needs. Those skills are still useful for those with the wherewithal and time to practice them.

What is absent in the Calendar are images of people interacting with modern technology, yet so many permaculture people I know interact with it every day, making modern tech as much about permaculture as the craft technologies.

Permaculture’s invisible systems

Let’s stop talking about photography and the philosophy of permaculture for a moment to consider the man who produces this calendar. Richard Telford.

It is through Richard’s gift of good graphic design that we have the calendar. And through his persistence in producing a new edition year after year.

Richard’s work amply demonstrates how publishing, photography and writing — all fall within the ‘invisible systems’ of permaculture — are as much permaculture skills as are growing cabbages or building a small house. Those are the skills through which we, as a social movement, get to know ourself. Without the skill of the photographer, permaculture journalist, author and publisher permaculture would remain ignorant of its challenges, its achievements, its story. It would have no story, no history. The Permaculture Calendar 2017 brings us a visual continuity of that history.

Here we are

Here we are

So, here we are. 2017… a new permaculture Calendar for a new year. A calendar that through the practice of photography records this design system that we inhabit and in doing so provides us with that sense of continuity I mentioned earlier.

But… Richard’s producing the Permaculture Calendar 2017 is only part of the story. Someone has to buy it this year if we want another calendar next year. Buying the Permaculture Calendar 2017 is a vote with our dollar for Richard to produce more editions. Our purchase money is the energy those future editions run on. Our purchase is a way to encourage Richard to produce the calendar over coming years.

What better Christmas gift could there be to remind those receiving it of permaculture’s accomplishments, month after month. We don’t actually need Christmas, however, for the calendar offers a way to say thank you to someone who has done us a favour, who has helped us out or whose work we value. It is recognition of another’s value in print form. In giving the calendar we give those receiving it the idea that there are other ways of doing things, there are alternative futures. And they are good.

How to purchase your Permaculture Calendar 2017 and other permaculture goodies.

Russ Grayson’s 2016 Permaculture Calendar Review / Russ Grayson’s 2014 Permaculture Calendar Review

Russ Grayson

Russ Grayson

Is an online and photojournalist living not far from the Pacific’s foaming breakers in coastal Eastern Sydney. He started freelance writing in Tasmania — something that has continued over the years in print, radio, photojournalism and online. After completing the communications degree at University of Technology in Sydney, he reported — and later edited — a business periodical for the then-emerging environmental industries, and assisted community-based organisations to produce their newsletters and journals.

Russ did one of the first Permaculture Design Certificates in 1985 , following up later with a Diploma in Permaculture Design in media. He and his partner organised an urban PDC that they ran for a decade, later joining the board of directors of Permaculture Australia. He is currently a passionate advocate for food sovereignty.

Russ is one of the contributors to Permaculture Pioneers: Stories from the New Frontier. You can check out the writings, the photographs, the memoir on the PacificEdge blog.