by Judith Turley and David Watson

by Judith Turley and David Watson

In the hills east of Canberra, down a dusty lane that passes racehorses dozing in thick phalaris, and wild apple trees and thickets of plum and hawthorn, then winds up the Lake George escarpment through Yellow Box woodland full of finches, thornbills, cuckoo-shrikes, kookaburras and robins, there’s a rusty old gate with a stencilled sign that says “Millpost”.

The heritage of our farm is long, complex and rich; challenging to protect in a time of climatic and economic uncertainty. As custodians for thirty-nine years, our family has endeavoured to preserve and enrich this landscape, while earning enough from the land to enjoy the privilege of maintaining stewardship. Permaculture Principle #3: Obtain a Yield

In January 1980 David and I attended the first-ever PDC at Stanley, Tasmania with Bill Mollison. The insights we gained have guided our decision-making ever since. Minimising food miles, creating stability through diversity, turning problems into assets, zero waste, small-scale and local solutions…these have been our bywords.

Millpost was windswept and degraded when David first arrived in 1979. Since then, we’ve planted or direct-seeded approximately 15 kilometres of native windbreaks using Eucalyptus, Acacia, Bursaria, Callistemon and Casuarinas.

Sheep are excluded from about 100 hectares, including riparian zones, to allow natural regeneration. Stock and wildlife alike benefit from shade and shelter in every paddock. Big increases in bird populations (135 sp.) mean improved natural pest control. But it’s not all good news; the resulting increase in kangaroo numbers threatens our viability.

Deciduous trees such as poplar, willow, oak, ash, honey locust and black locust are planted strategically to provide fire protection for the homestead complex, as well as stock fodder, shade and food (fruit and nuts). If they sucker, all the better!

Both native and exotic trees are harvested for timber (building and fence posts) and firewood (heating and cooking).

Both native and exotic trees are harvested for timber (building and fence posts) and firewood (heating and cooking).

By harvesting water from shed roofs uphill from dwellings, we use the Permaculture strategy of storing water at the highest possible point and using gravity to move it, rather than relying on pumps. We also place dams as high as possible in the landscape to enable gravity-feeding of water for stock or gardens. Principle #2:Catch and Store Energy.

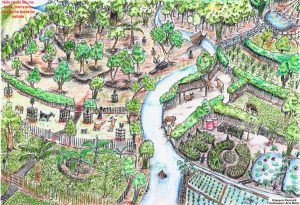

David Holmgren created a Whole Farm Plan for us in 1994. We are gradually implementing the design, moving from 8 large paddocks back in the 1970s to about 60 today, which we subdivide further with portable electric fencing. The new paddocks allow us to spell over 90% of the farm at any one time and to keep the sheep out of wet areas when necessary.

Survival in tough times

Our main challenge has been making a living from a relatively infertile farm, especially in frequent severe droughts. Our Permaculture system allowed us to survive low wool prices and other adversities because producing our own food (vegies, fruit, meat, eggs and dairy produce) has lowered our cost of living.

Today’s challenge is to provide a livelihood here for our children and their families. We hope our diversification venture, Millpost Merino knitting yarn, will help our family farm survive. Principle #8: Integrate Rather than Segregate

Our native pastures (more than 50% of the farm) are botanically diverse and yield well even in drought. Principle #10: Use and Value Diversity

Our native pastures (more than 50% of the farm) are botanically diverse and yield well even in drought. Principle #10: Use and Value Diversity

Bill Mollison told us the difference between conventional farmers and Permaculturists was that the former looked at the land and asked: how can this land be made to produce dollars? Whereas the latter asked: what does it (nature) offer? Principle #1: Observe and Interact

Sheep in Permaculture

Merino wool is the finest, softest wool in the world as a result of centuries of careful breeding programmes. Merino sheep can withstand climatic extremes and still produce this robust yet soft, multi-functional fibre for making clothing that can last a lifetime.

We are taking the Stewardship approach to our wool enterprise, by protecting and enhancing the endangered temperate native grasslands (including Grassy Yellow Box Woodlands) that make up much of the 1100 hectares of Millpost farm. Sheep are a regenerative tool: they graze pasture hard for short periods then move on to a fresh paddock, allowing grasslands enough time to recover between grazing events. Depending on seasonal conditions, paddocks may be grazed briefly only two or three times per year.

We are taking the Stewardship approach to our wool enterprise, by protecting and enhancing the endangered temperate native grasslands (including Grassy Yellow Box Woodlands) that make up much of the 1100 hectares of Millpost farm. Sheep are a regenerative tool: they graze pasture hard for short periods then move on to a fresh paddock, allowing grasslands enough time to recover between grazing events. Depending on seasonal conditions, paddocks may be grazed briefly only two or three times per year.

We are starting small, with only the very best of our fine wool clip (three bales) being processed for yarn. Principle #9: Use Small and Slow Solutions

David’s book Millpost: a broadscale permaculture farm since 1979 is available from our Australian webstore or from the yarn website millpostmerino.com.au